Throughout the African continent, many streets, buildings, and airports are named after him.

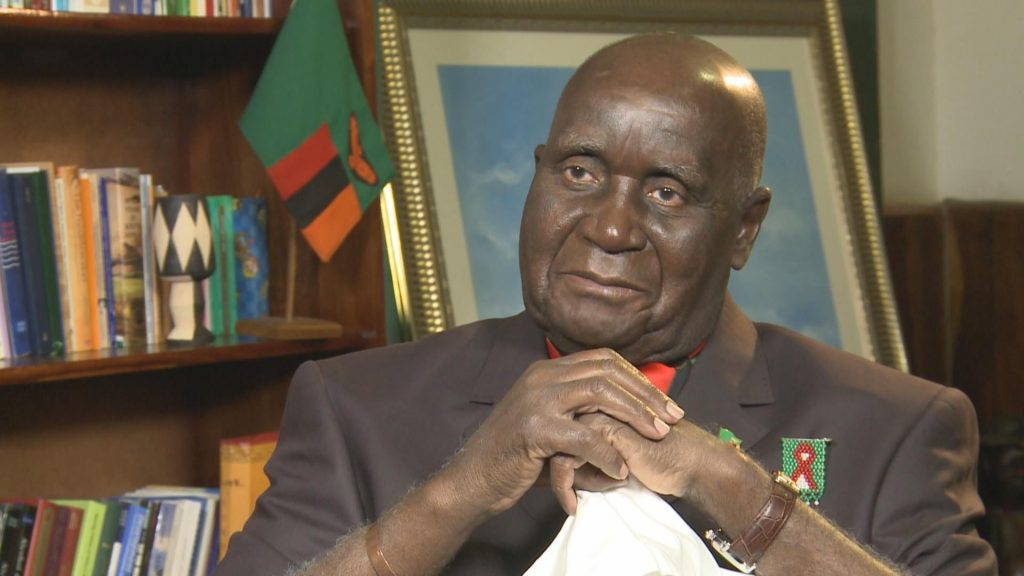

Unlike most independence heroes of their time, the name Kenneth Kaunda does not evoke bitter memories and feelings of alienation in different societies. His death on Thursday evening revealed a strong reverence that many across the globe had for one of Africa’s greatest patriarchs.

He was Zambia’s founding father, a liberation struggle hero, and a pan-Africanist. He even had a suit named after him – the “Kaunda suit” which echoes back to his favorite wear that consisted of a safari jacket paired with trousers.

As time went, so did Kaunda’s legacy appears to fade away as many Africans born after the end of colonialism had little memory or nostalgia for times that seemed so far away. Like many of his peers in the liberation struggle, he stayed so long that people got tired of him. Were it not for his foreign adventures, Kaunda would most likely have died a pariah in his own country that had previously fought to take away his citizenship immediately after he left office 27 years after independence.

Kenneth David Kaunda was born on 28 April 1924 in Chinsali, Northern Rhodesia, and was the youngest of eight children. His father was the Reverend David Kaunda, an ordained Church of Scotland missionary and teacher who was born in Nyasaland (present-day Malawi) and had moved to Chinsali to work in a nearby mission.

Kaunda began his political career as the organizing secretary of the Northern Rhodesia African National Congress (NRANC) in the Northern Province of Zambia. But in 1958, he broke from the NRANC to form the Zambian African National Congress (ZANC). The party was banned by colonial authorities a year later and Kaunda was imprisoned in Lusaka for nine months.

ZANC became the United Party for National Development (UNIP) in 1959, a center-left political movement that favored using non-violent methods of resistance to colonial rule, similar to Mahatma Gandhi’s struggle for independence in India in the 1940s.

Kaunda’s rhetorical skills endeared him to the public and he won independence for Zambia in 1964 without any bloodshed.

Upon gaining independence, Zambia’s education system was one of the most poorly developed in all of Britain’s former colonies, and the country had a total of just 109 university graduates and less than 0.5% of the population was estimated to have completed primary education.

As president, Kaunda instituted a policy where all children, irrespective of their parents’ ability to pay, were given free exercise books, pens, and pencils. The parents’ main responsibility was to buy uniforms, pay a token amount as a “school fee” and ensure children attended school.

Under the policy, the best pupils were promoted to achieve their best results, all the way from primary to university level. Kaunda also led the construction of the University of Zambia through a collective donation effort. The campus was opened in Lusaka in 1966.

Liberation movements

Kenneth Kaunda’s legacy will be most remembered in foreign affairs. He championed freedom from white minority rule in Namibia, Rhodesia, and South Africa, as well as independence for Angola and Mozambique from Portugal. He allowed the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), African National Congress (ANC), South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO), and its military wing, the People’s Liberation Army of Namibia, to set up camp there.

Joshua Nkomo, the leader of Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), and Oliver Tambo of the ANC spent most of their time living and working in Zambia.

Kaunda was one of the few African leaders to openly welcome the Soviet Union’s interventions in Africa, a key tenet of the socialism agenda he pursued. That angered the West who had become weary of Kaunda’s critiques of the United States for its war in Vietnam and calls for Britain’s suspension from the Commonwealth over what he termed as “London’s support for Rhodesia’s white minority rule.”

Kaunda was one of the first African heads of states to open the doors for Chinese investment in the continent despite staunch Western and Soviet objections. In the 1970s China sent tens of thousands of workers to build the 1,160-mile railway line linking Tanzania’s port city of Dar es Salaam with Kapiri Mposhi, a key industrial town near Zambia’s capital Lusaka. Zambia’s government saw the rail line as a major achievement providing relief from the sanctions on trade applied by white-minority governments that ruled neighboring countries.

But while the rail line is still operational today, it has never managed to pay back its debt more than 50 years later.

The Peacemaker

While Kaunda was a revolutionary, he often dangled the diplomatic card as well. He was the driving force behind the Lusaka Manifesto of 1969, in which the white-minority regimes were offered a chance of either negotiated settlements or armed struggles.

Kaunda also played a leading role in mediating among contending Zimbabwe nationalist groups in the late 1970s. Having long favored Joshua Nkomo and ZAPU, he helped forge the Patriotic Front, an alliance in which Nkomo joined forces with his longtime rival Robert Mugabe of ZANU.

The Patriotic Front acclaimed international support, paving the way for peace talks that later led to the independence of Zimbabwe in 1980.

In April 1982, Kaunda met with South African Prime Minister P. W. Botha near South Africa’s border with Botswana urging him to release Mandela, the African National Congress leader, from prison. He repeated the same plea seven years later while hosting a meeting with South Africa’s new president F. W. de Klerk. Klerk did not respond to his request but in memoirs published later on he characterized Kaunda as “an honest Christian” and “a pleasant man”

But Kaunda’s label as a peacemaker was challenged when he staunchly defended Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe’s policy of land reform, under which white farmers were driven away from the country and their land confiscated by the state, contrary to the Lancaster House talks that led to independence.

“I’ve been saying it all along, please do not demonize Robert Mugabe. I’m not saying the methods he’s using are correct, but he was put under great pressure,” he said.

Economic woes

In its independence year (1964), Zambia had the largest economy in sub-Saharan Africa. However, by the time Kaunda left office 27 years later, Zambia had become one of the most indebted countries in the continent.

Kaunda’s government was responsible for much of the economic woes the country faced. They failed to diversify the economy that could have withstood the fall in copper prices in the 1970s and the nationalization of mining companies was wrongly executed.

While copper had proved a blessing for Zambia leading the country to have the highest GDP per capita income in the continent in 1968, reliance on the metal also made the country dependent on fluctuating international markets. Zambia’s geographical location as a landlocked country whose crucial economic supply lines went through white-minority ruled territories exacerbated its vulnerability.

Rhodesia led by Prime Minister Ian Smith cut off its rail links that had historically carried Zambian copper ore to ocean ports and world markets. The Central African country was also regularly bombed by Rhodesian and South African forces on missions to root out guerrillas that were operating on their soil, including many from South Africa’s banned African National Congress. In the 1970s and 80s, Zambians formed long lines to acquire basic food supplies.

Kaunda’s government also took ill advised decisions to borrow so much from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) leading Zambia to accumulate more debt than any other country on the continent. When he ignored IMF’s proposal for an austerity program, other lenders reduced their aid further squeezing the economy.

Kaunda’s economic polices later fueled disgruntlement among many Zambians who began clamoring for multiparty democracy.

The end of his reign

Throughout his stay in power Zambia was a one party state with little room for freedom of expression. Kaunda banned political opposition in 1973 after interethnic clashes broke out.

Inevitably, years of economic decline and international isolation led to cracks in his rule. There were frequent reports of attempts to overthrow the government and a dusk-to-dawn curfew was imposed over much of the country in late 1980.

Further attempts to dislodge him from power continued over the next decade, the last of these in 1990 followed food riots in Lusaka and the Copperbelt region over the government’s crash austerity programme.

His image of a man of peace was further tainted by the killing of 20 people in the three days of rioting and the storming of the campus of Zambia University by security forces.

While Kaunda saw himself as very important to Zambia, his people didn’t. Pressure was mounting to introduce the multiparty democracy he advocated for in neighboring countries. Eventually he agreed and called elections on 31 October 1991.

He lost the presidential elections to Fredrick Chiluba from the Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) after a fiercely contested campaign. Kaunda accepted defeat waving his trademark white handkerchief.

After handing over power peacefully, Kaunda continued to engage in national politics and in 1996, he tried to stand for presidency. Viewing him as a threat, the Chiluba government changed the constitution so that anyone whose parents came from outside the country was deemed a foreigner and could therefore not run for office. Kaunda, whose father was born in Malawi, fell afoul of the new rule.

In November of that year, four gunmen shot and killed his 47-year-old son, Wezi, in the driveway of his home in Lusaka. The younger Kaunda, a retired army major, had been a rising figure in his father’s opposition United National Independence Party and widely seen as an heir to the throne.

Many suspected the incident was an assassination attempt though the government described it as a carjacking.

Chiluba later attempted to deport Kaunda alleging that he was a Malawian. In 1997, Chiluba threw Kaunda in jail on Christmas Day for allegedly being involved in a foiled coup attempt.

He was declared stateless by a Zambian High Court, but he challenged this decision in the Supreme Court of Zambia, which declared him to be a Zambian citizen the following year.

Kaunda’s time in politics had come to an end. He became a strong AIDS campaigner, announcing publicly the death of one of his sons to the disease. Being away from the muddy fields of power elevated his persona to a revered statesman figure involved in mediation and dialogue efforts across the continent.

For a man who fought for freedom and independence, Kenneth Kaunda became a victim to the right to vote. While he helped other countries prosper, Zambians wonder whether that was a worthy price to pay as the economy deteriorated and Africa’s wealthiest nation became one of its most indebted.

Testament to his legacy, Kaunda remains respected across Africa even amongst a generation that is questioning the deity status given to their founding fathers. Perhaps, it is because he was that good, or better than most of his peers.