Mobile money has often been touted as the greatest innovation in Africa’s financial space – and rightly so. Its introduction at the start of the new millennium reenergized economies reeling from the slow macroeconomic growth induced by the IMF-backed structural adjustment programs (SAPs) in the late noughties. With the ease of their mobile phones, large chunks of the masses locked out of the traditional banking systems could send and receive money easily.

Today, Africa accounts for 70% of the world’s $1 trillion mobile money value. The value of mobile money transactions skyrocketed by 39% to $701.4 billion in 2021, from $495 billion in 2020. But as mobile money grows, other new approaches to digital transformation and financial service provision are slowly gaining ground. They could even overtake to become the primary means of making payments soon.

Just like mobile money, cryptocurrencies have gained acceptance among a large proportion of low-income earning demographics. Although the continent receives just 2% of the global value of all cryptocurrencies, their rapid growth over the last three years is immense.

A recent report by Chainalysis, a blockchain data platform, found that between July 2020 and July 2021, Africans received $105.6 billion worth of cryptocurrency, an increase of 1,200% from the year before. Meanwhile, several African countries are looking to use central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) to overcome infrastructural problems affecting the banking sector.

The success of mobile money

When Naomi Gitau finished school in 2017, she thought she would easily land a job in one of the many swanky hotels that litter Nairobi’s urban space. But after months of trying without success, she decided to open a grocery business in Juja, a small town located 35 kilometers away from the busy capital.

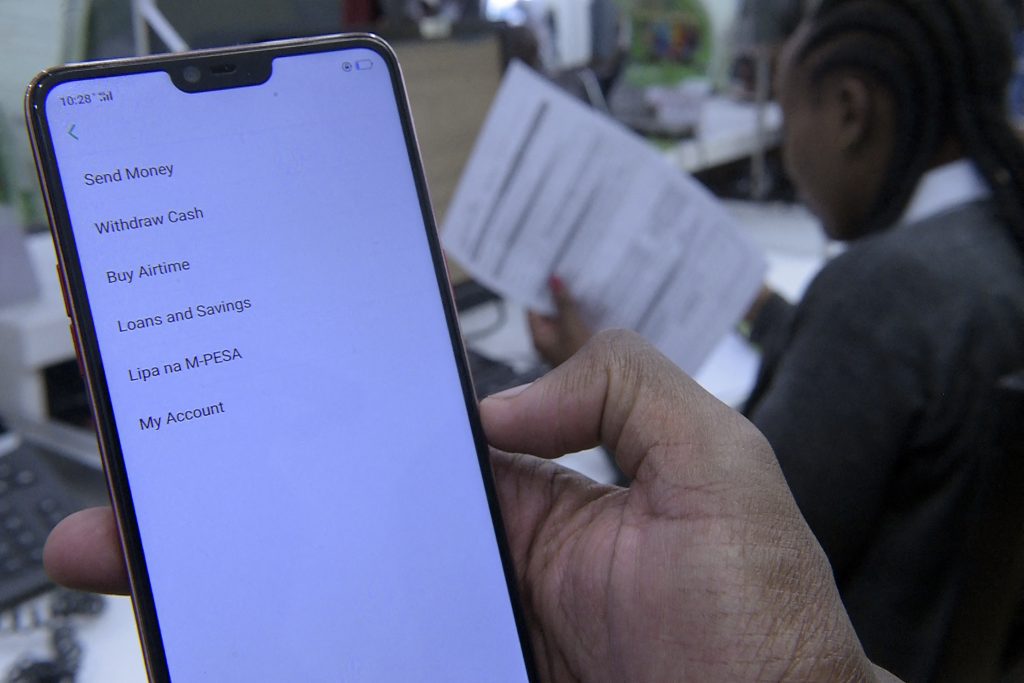

For Naomi, her business is heavily reliant on the mobile money service named MPESA. Not only does she use the platform to pay for new stock, but her customers mostly choose to send her money instead of paying through cash.

“I don’t like it because it gives me trouble to account,” she says. “Because most want to MPESA me, I cannot refuse. Every seller today uses it (MPESA).”

Millions of small-scale traders like Naomi have become ardent followers of the mobile money revolution. It could be argued that the invention of MPESA in 2007 resurrected this sector, opening new channels of doing business for those who were financially marginalized.

For all its successes, mobile money has never stopped growing in Africa. Figures from GSMA indicate that the volume of transactions jumped 23% to 36.7 billion in 2021, from 27.5 billion in 2020. In the review period, registered mobile wallets in Africa topped 621 million, a 17% increase from the 562 million captured in 2020. Currently, there are over 184 million active mobile money wallets on the continent compared to 161 million accounts just over a year before.

“As a result, businesses and individuals alike have benefited from this fast-paced digitization of payments, unlocking access to more products and services, building financial resilience, and bringing about commercial opportunities,” Ashley Olson Onyango, Head of Financial Inclusion at GSMA, said.

The African mobile money ecosystem is also rapidly diversifying as is the rest of the world, from business-to-consumer (B2C) to business-to-business (B2B.)

“A key feature of the industry’s progress in the past years has been mobile money’s rapid diversification beyond its key traditional use case: person-to-person transactions (for example transferring money to family and friends),” Ashley Onyango added.

However, the high transaction fees remain a key challenge.

Cryptocurrencies

For all its simplicity, swiftness, and timeliness, mobile money embodies a few weaknesses that have opened the door to the rise of crypto. Crypto transactions are more secure since they do not pass through formal systems. Unless someone gains access to the private key for your crypto wallet, they cannot sign transactions or access your funds.

They also facilitate transparency since the transactions take place on a publicly distributed blockchain ledger. Anyone can look up the transaction data and verify the details.

The value of crypto has been growing so fast – even though not at the rate of mobile money – to illustrate that it could become the primary means of making payments in the future. In August 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Sub-Saharan Africa traded $18.3 million of the $95 million total worth of bitcoins traded globally in one week – the second highest trading volume after North America (at $28.7 million).

In 2019, out of the $48 billion remitted to sub-Saharan Africa 2019, Chainalysis estimates that up to $562 million worth of remittance payments were facilitated by cryptocurrencies such as Ripple. Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya lead the adoption of crypto globally.

Bitange Ndemo, a former Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of ICT in Kenya, and now a Professor of Entrepreneurship at the University of Nairobi, is a fan of this innovation. He has been one of the leading voices in the continent pushing for governments to set up regulations that will facilitate the growth of crypto.

“Because cryptocurrency platforms bypass traditional banking services by introducing decentralized peer-to-peer lending services, they can help level the economic playing field and expand finance options to underserved customer markets,” he wrote in his blog post.

Challenges

Despite the recent gains, several challenges hinder the adoption of cryptocurrencies in Africa. Chief among them is financial literacy. Unlike the simplicity of mobile money, transacting in crypto requires sufficient knowledge of blockchain technology and crypto itself. Worse, crypto has been hit by the accusation of being a “scam”, particularly by the older generation who enjoy formal employment and rely on formal banking systems. Thus educating the public has become nay impossible.

Another major challenge is the lack of traders accepting crypto as legal tender. There are not many businesses or vendors who accept payments in crypto in Africa. However, almost all of them accept mobile money payments. Mobile money succeeded because it had no rival. Most users were previously locked out of the traditional banking systems. Crypto is now coming into a pretty congested space.

African countries are also fearful that digital currencies could pose a potential threat to monetary sovereignty. The fear is that should crypto become more widely used than domestic fiat currency, national monetary agencies such as central banks may not be able to steer their economies to a path of growth using monetary policy.

Professor Bitange Ndemo, however, argues that should not be the case.

“Government cannot shut the stable door after the horse has bolted. Blockchain technologies are the future, and any effort to ban them—or even excessively intervene in their operations—would meet the same fate as other state attempts to circumscribe behavior.”

“Moreover, restricting cryptocurrencies at the moment, when they are facilitating innovations and brimming with potential, would undermine financing of critical sectors like MSMEs, affordable housing, and remittance payments right when Africa needs these options most.”

Some countries like Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal, and South Africa have crypto exchanges but no regulatory framework. Meanwhile, Botswana, Kenya, and Zimbabwe have allowed trading but do not provide an exchange. The African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement (AFCFTA) is numb on this issue, despite the potential of crypto being the flag bearer for transactions in the new free trade area.

Digital Currencies

CBDCs are digital versions of cash that are more secure and less volatile than crypto assets because they are issued and regulated by central banks. By using the technology behind cryptocurrencies, they aim to bring financial services to the hundreds of millions of Africans without bank accounts, facilitate domestic and cross-border payments, and stabilize inflation.

“The CBDC model will be very advantageous for Africa because it allows anybody to trade, it doesn’t need an internet connection, financial policies can be implemented much quicker, taxation and accountancy are simplified, and, most importantly, in CBDCs there are no fees of transfer,” says Dennis, whose company advises central banks in Africa on how to implement the CBDC model.

Already several African countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia are exploring the prospects of launching their Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs).

Nigeria has already taken the lead and launched its digital currency, the eNaira. According to the Central Bank, this digital version of the Naira holds similar value to the fiat currency. Users can swap their eNaira for the physical Naira at the same time, with the caveat being that the eNaira can only reside in their phone wallets.

Perhaps as a precursor to the challenges CBDCs face, the eNaira mobile wallet did not survive long on Google Playstore. It faced plenty of user backlash that led to Google taking down the application. Many people viewed it as an attempt to curb the popularity of crypto in the country since, before its launch, Nigeria’s government banned the trade of cryptocurrencies. The central bank even ordered the closure of accounts of individuals trading cryptocurrency.

On the other hand, Ghana and South Africa are currently running pilots for their CBDCs.

The South African Reserve Bank is experimenting with a wholesale CBDC, which can only be used by financial institutions for interbank transfers, as part of the second phase of its Project Khokha. The country is also participating in a cross-border pilot with the central banks of Australia, Malaysia, and Singapore.

The Bank of Ghana, by contrast, is testing a general purpose or retail CBDC, the e-Cedi, which can be used by anyone with either a digital wallet app or a contactless smart card that can be used offline.

Sub-Saharan Africa ranks as the most expensive region to send and receive money, with an average cost of just under 8% of the transfer money. While, CBDCs could make sending remittances easier, faster and cheaper by shortening payment chains and creating competition among service providers, there is a long way to go. Governments will need to improve access to digital infrastructures such as phones or internet connectivity. More investment will be required to increase the technical capacity of central bank officials to manage the risks involved.

Mobile money defined the last decade of Africa’s renaissance story. Although it will remain a major player in the future of payments, there is a significant possibility that cryptos and Central Bank Digital Currencies will also be part of this conversation. That only spells good news for financial inclusion.