As the United Kingdom celebrated in remarkable grandeur Queen Elizabeth’s platinum jubilee, far away in Africa, a mini commemoration was taking place. For many people outside Kenya, Nyeri is not a town they may be aware of. However, in June, this tiny agricultural town, located 94 miles north of the capital Nairobi, was thrown into the limelight as its unique story was told.

Nyeri is where the young Elizabeth became Queen 70 years ago. At the time, the town was a famous hotspot for British elites and high-spending tourists. When Elizabeth came to Kenya for a holiday trip, which turned out to be the marquee moment of her life, the country was a British colony. She and her husband, Prince Philip, had almost skipped that leg of their tour because the colony was already in the early stages of the armed Kenya Land and Freedom Army peasant rebellion – that the world would come to know as the Mau Mau uprising. Governor Evelyn Baring had also declared a state of emergency.

Today, Nyeri is a Western-styled town with good infrastructure and a strong economic base due to the huge plantations of cash crops on nearby farms. But Nyeri also bears the scars of a battle waged by the very people who built it up. Between 1953 and 1955, the Royal Air Force dropped over 6 million bombs on Kenyans fighting for independence. Over 1.5 million of the inhabitants of Nyeri, and the surrounding areas that make up the Mount Kenya region, were imprisoned in camps. The story of Nyeri is quite symbolic of the legacy that the British monarchy, and Queen Elizabeth, its long-term figurehead, leave behind.

The monarchy’s deadly deception

For years, Queen Elizabeth has cultivated a charming and flashy image. Her style, wardrobe, and demeanor have been adored the world over. Despite her laidback, I-cannot-do-any-harm appearance, she was once a vibrant leader who defended Britain’s place in a rapidly changing world.

Queen Elizabeth stepped into the throne when the British Empire was fast declining. It had lost its largest possession – India and Pakistan – five years earlier, and the winds of independence were sweeping across Africa. In the 1950s, Britain was weakened. The fight against Nazi Germany had taken a heavy toll on its infrastructure. The economy was sunk into debt levels never seen before. As thousands of Britons lined up for food rations along the streets, they began questioning the value of maintaining territories in far-flung areas of the world. Thus the monarch, which had once had dominion over so many portions of the Earth that it was said famously that the sun never set on the British Empire, quickly had to reinvent themselves.

Addressing the House of Commons in July 1943, the then Secretary of State for the Colonies, Oliver Stanley, declared that his Government was “pledged to guide Colonial people along the road to self-government within the framework of the British Empire.”

However, decolonization was not as smooth as promised. Liberation movements used the tactics they had learned while fighting the Allies’ wars in Burma and North Africa to conduct grueling battles against the colonial army.

Decolonization in Africa began with the Gold Coast, which achieved independence from Ghana in 1957. Despite granting power to African hands, the imperial legacy remained in the form of a governor-general, who represented Queen Elizabeth as the country’s formal head of state and sovereign. After plenty of pushback, Ghana transitioned to the status of a republic in 1960 with Kwame Nkrumah becoming its first president and head of state. This tactic was replicated in all British African colonies over the course of the following two decades.

During the years after decolonization, the monarchy sought to influence the foreign policy and trade relations of the newly independent states. One key target was Ghana, led by President Kwame Nkrumah, whose ties to socialism caused angst in London and Washington that Africa might become fully entrenched in the Soviet bloc. Thus in 1961, Queen Elizabeth decided to make an official visit, intriguingly one of the few she has made to the continent during her reign.

“The British government was certainly concerned to limit Soviet influence in ex-colonies,” John Parker, a historian at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African said. “Overseas tours by the queen were designed broadly to strengthen Commonwealth links.”

It is there that the Queen, in a moment that would reverberate forever, danced with Kwame Nkrumah at a ball party in Accra. Shortly after, a cable was sent that the Ghanaian head of state had accepted London’s overtures. It set into motion the strong trade and economic ties that the continent would soon enjoy with its former colonial power.

Her legacy endures in the present

Elijah Nyakiangana is the Executive Director of the Association of Policy Practitioners, a body that brings together young policy professionals in Kenya. He traces the retrogressive laws that have promoted human rights abuses and autocracy in the continent to the colonial era.

“The Queen’s era promoted retrogressive laws like the Penal Code that are still entrenched in our legal system. This has denied Kenyans justice in the form of arbitrary arrests and detention.”

Cultural ties between Africa and the United Kingdom remain strong. According to the United Nations, over 350 million Africans speak English.

“We also have imperialism in the continent that exists through the advancement of British culture, language, at the behest of our own traditional cultures.”

Affinity to Britain was fostered by the first generation of leaders through their education or religious involvement with its institutions. Hastings Kamuzu Banda of Malawi was an elder in the Church of Scotland, Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia was the son of a Malawian Church of Scotland missionary, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania studied at the University of Edinburgh, and Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya studied at the London School of Economics.

In the years post-independence, the United Kingdom has offered tens of thousands of scholarships to Africa’s brightest young minds. The United Kingdom remains the biggest investor in the continent, according to UNCTAD, ploughing over $56.3 billion last year.

Since 2015, British forces have supported Nigeria in the fight against Boko Haram. UK forces are also supporting the French-led Operation Barkhane against extremist groups in the Sahel.

London has also signed a refreshed UK-Kenya Security Compact to counter the threat posed by Al-Shabaab in the Horn of Africa. Britain’s military still maintains its bases in Kenya, where some of its soldiers have been accused of impunity.

However, Queen Elizabeth’s reign has coincided with a sharp decline in trade ties with the continent. Africa accounts for just 2.5% of UK’s trade. This percentage is largely skewed by South Africa and Nigeria, the continent’s two largest economies, who both make up 60% of the entire UK-Africa trade relationship.

As Britain idled, China swept in. Ghana, Zambia, Kenya, Zimbabwe all share China as their largest foreign trading partner.

Unhealed scars of the past

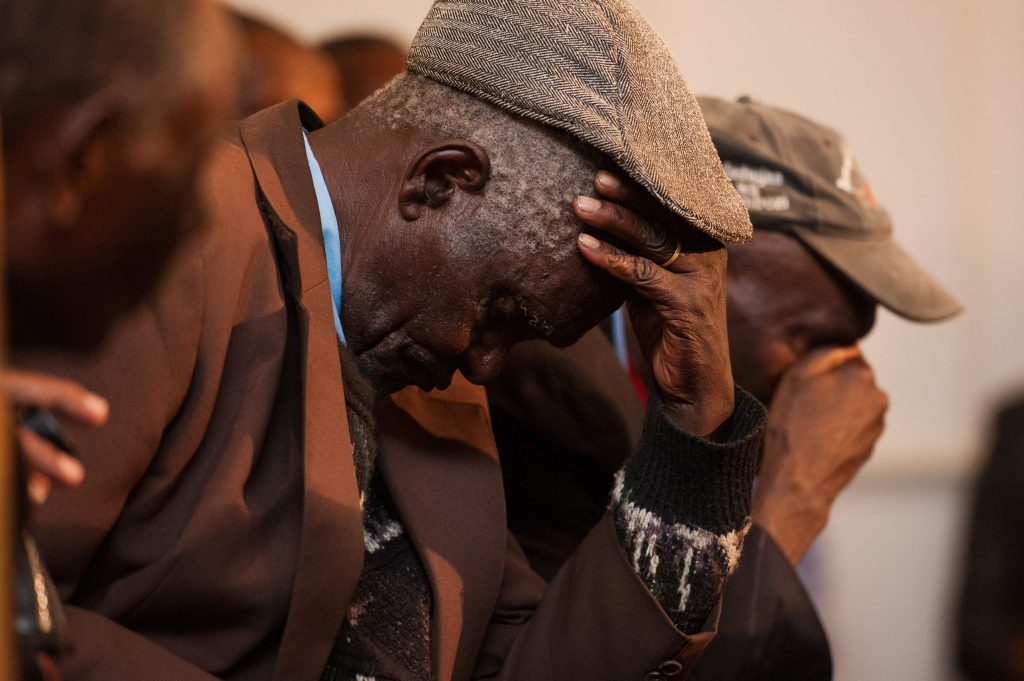

As Queen Elizabeth celebrated her platinum jubilee, another old Kenyan grandmother was marking an auspicious moment, albeit filled with unhealed wounds caused by the rule of the former.

Muthoni Mathenge spoke to German media station, Deutsche Welle (DW), detailing the negative experiences she underwent and demanded that the Queen compensate her in cash. She claims she was tortured by British troops in 1952 after they had stormed her house in search of her husband, who was part of the Mau Mau, a banned liberation movement.

“When they came looking for him, I told them that I had not seen him for days. I refused to tell them because snitching your own whereabouts of fighters would amount to death.”

Muthoni displayed marks on her right foot as proof of torture. She added: “Let (Queen) Elizabeth bring what belongs to me, no middlemen in between. Let the compensation come directly to me. Let her give me a just compensation because she is the ruler.”

She was tortured with axes during Kenya's struggle for independence from British colonial rule.

— DW News (@dwnews) June 1, 2022

As the Platinum Jubilee of the British monarch draws near, this old fighter wants to send her a message: "Let Elizabeth bring what belongs to me." pic.twitter.com/SDWSYwIqmg

It is no secret that the royal family has always been fascinated with Africa. Even today, their footprints can be found in the thousands of initiatives they sponsor, ranging from wildlife conservation to scholarships and sustainable development projects.

Cue Elizabeth becoming Queen of Kenya. Prince William proposed to Kate Middleton at a secluded cabin gateway in the sprawling Lewa Wildlife Conservancy in Kenya. “Kenya has always been very close to Prince William’s heart. He’s been coming here for many years. He loves it,” said British national Ian Craig, founder of Lewa and owner of the cabin.

William first went to Kenya during his gap year at age 17 and has returned several times. Kenya, he has said, provides a respite from real life.

“It’s escaping to a kind of different world where I am just who I normally am anyway, and I can let that side, that sort of slightly immature, silly person come out a bit more than I normally do,” he said.

“This is a royal family that wants to engage with Africa, understands its challenges but recognizes that it’s a beautiful place and wants to show the world,” said Ayo Johnson, director of Viewpoint Africa, which sells content about Africa to media outlets internationally.

But the royals appear to be drawn to a certain image of the continent – one of the stunning landscapes and peculiar cultures. Neither Queen Elizabeth nor her descendants have ever acknowledged, apologized, or sought to make amends for the horrors visited upon Kenyans in her name. The $25 million grudgingly paid out to just 5,000 Mau Mau veterans in 2013 was a pinch of salt to their wounds. In contrast, 190 years ago, Britain used 40% of its national budget to compensate slave owners – not slaves – following the formal abolition of slavery.

Jamaican historian Rosalea Hamilton highlights the collective oblivion of the crimes of British colonization, in Africa and elsewhere. “When you think of the Queen today, you think of a nice old lady,” Hamilton quips, “but her family’s fortune was built on the backs of our ancestors. We are grappling with the legacies of a very painful past”.

Queen Elizabeth and the Commonwealth

Even though the Queen is a ceremonial figure in UK’s governance structures, she is still the head of the Commonwealth. Testimony to declining trade ties with its former colonies, Queen Elizabeth’s pet project is limping to an evident conclusion.

The Commonwealth has remained a largely ineffective organization that once in a while holds a summit to remind of its presence. Membership carries few economic benefits and unlike Lusophone nations who enjoy free movement to their former colonial master Portugal, UK has never afforded similar privileges to its former colonies.

A recent UK-Africa trade summit produced little and the secretariat and its development arm have seen their budgets slashed in recent years.

Queen Elizabeth will be buried in yet another grandiose event that will likely be attended by many world leaders. As her longevity on the throne is remembered, it is vital that her contradictory yet deceptive legacy on the African continent is pondered upon.