At the just concludedGlobal Commodities Forum in Geneva, Switzerland, policymakers yet again deliberated on numerous issues that have plagued developing nations with particular emphasis on commodity exporters in the wake of arguably the economic shock of the century. As the ‘green energy transition’ train gains steam however, it came as no surprise that a session on the green energy transition was on the programme.

But credit need be bestowed where it is due. See, over the past decade, major global economies devoted nearly 16 per cent of their total fiscal stimulus to “green investments.” Many of these took were in form of low-carbon energy, energy efficiency, pollution abatement and materials recycling, natural-resources conservation and environmental compliance.

Nevertheless, today, the green economy is at a critical crossroads. On one end, has the potential to foster a new wave of economy buoyed by wide innovation, employment, and green growth while on the other end, some are worried that if not is not done soon enough, it may be relegated to a niche within an overall ‘brown’ economy. A critical matter to address today is the policy void which continuously cripples the green transition on three fronts. That is; environmentally harmful subsidies, inadequate market-based incentives, and insufficient public support for private research and development. A policy strategy for green growth requires phasing out and rationalizing subsidies, instigating effective market-based instruments, and allocating the revenues raised to enhance green innovation.

In order to achieve a hasty transition to green energy, we need to be asking ourselves how to transition the world’s energy infrastructure away from gas and coal, while also meeting dramatically increased overall global demand. This is by far the most challenging question of them all. Policymakers need devise a means to remove polluting fuels from the energy mix of their respective nations and this is where it gets complicated. See, over the past 20 years, global energy consumption has increased by over 45% and with this demand, coal too has picked up. More frustrating is the fact that some governments which rely heavily on coal have in the past refused to endorse scientific advice on climate change.

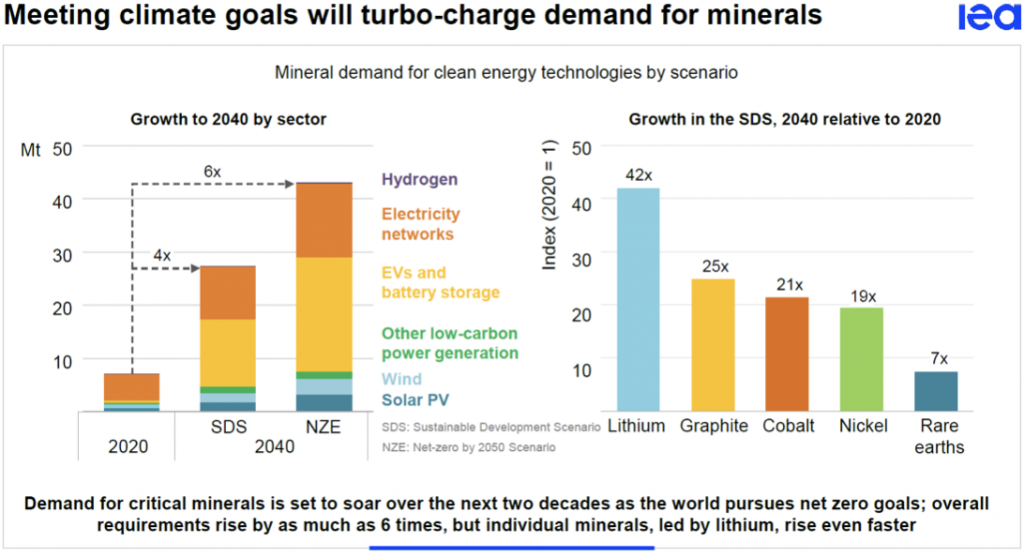

A daunting revelation at the Global Commodities Forum was the fact that demand for specific minerals is expected to rise at rates never seen before exposing the sector of renewable energies to potentially disruptive market tensions. For instance, solar photovoltaic (PV) plants, wind farms and electric vehicles (EVs) generally require more minerals to build than their fossil fuel-based counterparts. Now given the energy policies changes taking shape across the world, the laxation of the regulatory framework could lead to a doubling of overall mineral requirements for clean energy technologies by 2040 given the heightened production.

Amidst the impending binge in global demand for critical minerals, unless governments do away with the environmentally harmful subsidies, the green energy transition may take longer than expected. The persistence of fossil-fuel subsidies is an example of environmentally harmful subsidies that are slowing the development of the green economy. Recent studies have revealed that they have the ‘triple-whammy effect’ of creating economic inefficiencies in production, distorting market prices to make fossil fuels artificially cheap relative to clean energy sources, and increasing environmental damages and health effects from pollution. However, the persistence of fossil-fuel subsidies and other environmentally damaging subsidies, such as in agriculture and transport, creates another problem as the same subsidies for a basis for the implementation of environmentally motivated subsidies as the main policy for fostering the green economy. The reasoning being that the environment subsidies would counter the price advantage that environmentally harmful subsidies give to the brown economy, and subsequently promote the expansion and employment in the emerging sectors of the green economy.

Ultimately, renewable energy has a critical role to play in the structural transformation of developing economies, becoming a potential catalyst for innovation. More so, with forecasts showing that renewable energy has the potential to account for more than 60 per cent of the global increase in electricity output by 2023, the falling cost of renewables could play a key role in getting electricity to more businesses and homes in developing countries, especially those outside the main cities by far justifying the need for a transition in our lifetime.