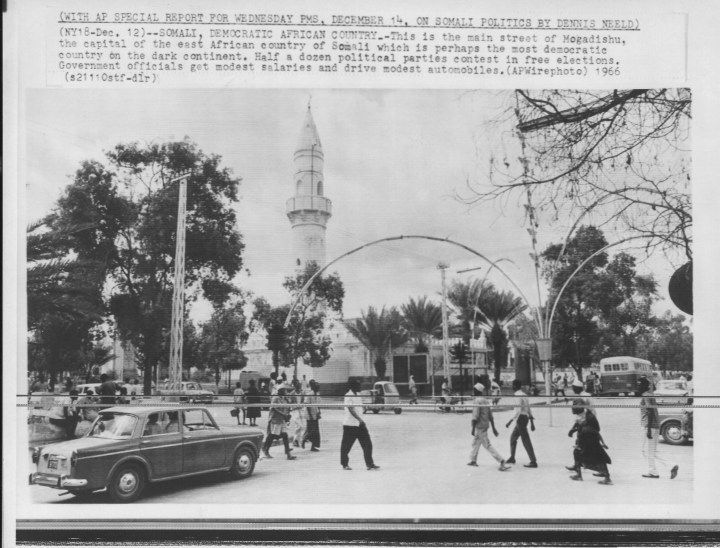

There is a common adage that time is a healer, but in Somalia, memories of times gone by evoke painful memories of the good old days in both the elderly that witnessed them and the young who can only fathom such glories.

To know how much has changed in this country, picture this. In 1967, while most African countries were either fighting for independence or had founding fathers suppressing dissent in order to consolidate power around their base, Somalia held the continent’s first democratic presidential elections. Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was overwhelmingly elected president.

Before that, there was the historic first of a nationwide referendum in 1961, as Somalians approved a new constitution.

But the rollercoaster never lasted that long. As a possible signal of what is to come, President Shermarke was overthrown in a military coup in 1969, and since then democracy has never returned to Somalia.

A civil war that started in 1991 after the ouster of President Siad Barre, who himself removed Shermarke from office, has never stopped, and the government despite military support from the U.S., Turkey, and African Union doesn’t not govern much of the country.

However, in 2021, President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, popularly known as Farmajo, is hoping to change that albeit with limited success so far.

Attempts to hold a free and fair election acceptable to all political players has hit a dead end after leaders across the divide failed to reach consensus in meetings held in the city of Dhusamareeb.

President Farmajo had earlier pledged to hold a nationwide one man one vote poll, but it quickly became clear that was not possible as the government lacks authority over large tracts of the country.

Thus, he has assured lawmakers there won’t be a power vacuum when his tenure ends of February 8. But there are no publicly available details about how this could be achieved if the vote is delayed.

The current impasse was partly sparked by the federal state of Jubaland and the semi-autonomous region of Puntland after they both refused to sign a pact introducing a new electoral model, according to Farmajo. A group of presidential aspirants also disagreed with the planned process and said electoral commission officials appointed by the head of state were partial.

The president said he remains hopeful that all stakeholders will accept the electoral model reached in September last year and proceed with negotiations to overcome the impasse as soon as possible.

Farmajo is a frontrunner in the vote that’s attracted many other candidates, including former presidents Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed and Hassan Sheikh Mohamoud and former Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khaire.

Al-Shabaab

Hovering over Somalia’s poll is Al-Shabaab. The Islamist militant group still controls large tracts of southern Somalia despite the presence of Kenyan, Burundian and Ugandan troops in the area as part of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISSOM).

Residents such as Mohammed Burji admit privately that a significant number of Somalis once supported Al Shabaab’s policies. “They were not corrupt like the government and they served the people. I think if you were to ask people privately whom they prefer between Al Shabaab of ten years ago and the government of today, the choice is clear.

“But that support has reduced over the years because they have been killing many people.”

Al-Shabaab began in late December 2006 as a splinter group of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), after the ICU peacefully withdrew from Mogadishu and its leaders Sharif Sheikh Ahmed and Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys resigned and disbanded the union.

The earliest recorded attack which Al-Shabaab claimed responsibility for was a suicide car bomb in Mogadishu in March 2007, conducted against Ethiopian troops who were occupying Mogadishu at the time. The killing of 73 Ethiopian soldiers enabled the militant group gain large support among a populace that was united against the occupation and disenchanted by atrocities carried out by Ethiopia’s army.

Al-Shabaab was later pushed out of the capital by AMISSOM troops but since then has managed to carry out hundreds of terror attacks that have claimed the lives of thousands of innocent Somalis.

Last month, the United Nations said Somalia’s election date of Feb. 8 was impractical for the nation struggling to set up a stable government after decades of civil war and amid an Islamist insurgency. The vote “seems unrealistic at this time,” said James Swan, the UN secretary-general’s special representative to the country. “This is a complicated endeavor.”

With no end in sight to the violence, a new government may choose to seek a political solution and not a military solution, following in the footsteps of the Afghanistan war, where America after two decades of fighting the Taliban is now engaged in peace talks over a permanent end to it’s longest and costliest war.